mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-13 22:30:37 +08:00

submit tech/20180521 An introduction to cryptography and public key infrastructure.md

This commit is contained in:

parent

5fca0b4fce

commit

01b20004a7

@ -1,108 +0,0 @@

|

|||||||

pinewall translating

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

An introduction to cryptography and public key infrastructure

|

|

||||||

======

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Secure communication is quickly becoming the norm for today's web. In July 2018, Google Chrome plans to [start showing "not secure" notifications][1] for **all** sites transmitted over HTTP (instead of HTTPS). Mozilla has a [similar plan][2]. While cryptography is becoming more commonplace, it has not become easier to understand. [Let's Encrypt][3] designed and built a wonderful solution to provide and periodically renew free security certificates, but if you don't understand the underlying concepts and pitfalls, you're just another member of a large group of [cargo cult][4] programmers.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Attributes of secure communication

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The intuitively obvious purpose of cryptography is confidentiality: a message can be transmitted without prying eyes learning its contents. For confidentiality, we encrypt a message: given a message, we pair it with a key and produce a meaningless jumble that can only be made useful again by reversing the process using the same key (thereby decrypting it). Suppose we have two friends, [Alice and Bob][5], and their nosy neighbor, Eve. Alice can encrypt a message like "Eve is annoying", send it to Bob, and never have to worry about Eve snooping on her.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

For truly secure communication, we need more than confidentiality. Suppose Eve gathered enough of Alice and Bob's messages to figure out that the word "Eve" is encrypted as "Xyzzy". Furthermore, Eve knows Alice and Bob are planning a party and Alice will be sending Bob the guest list. If Eve intercepts the message and adds "Xyzzy" to the end of the list, she's managed to crash the party. Therefore, Alice and Bob need their communication to provide integrity: a message should be immune to tampering.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

We have another problem though. Suppose Eve watches Bob open an envelope marked "From Alice" with a message inside from Alice reading "Buy another gallon of ice cream." Eve sees Bob go out and come back with ice cream, so she has a general idea of the message's contents even if the exact wording is unknown to her. Bob throws the message away, Eve recovers it, and then every day for the next week drops an envelope marked "From Alice" with a copy of the message in Bob's mailbox. Now the party has too much ice cream and Eve goes home with free ice cream when Bob gives it away at the end of the night. The extra messages are confidential, and their integrity is intact, but Bob has been misled as to the true identity of the sender. Authentication is the property of knowing that the person you are communicating with is in fact who they claim to be.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Information security has [other attributes][6], but confidentiality, integrity, and authentication are the three traits you must know.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Encryption and ciphers

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

What are the components of encryption? We need a message which we'll call the plaintext. We may need to do some initial formatting to the message to make it suitable for the encryption process (padding it to a certain length if we're using a block cipher, for example). Then we take a secret sequence of bits called the key. A cipher then takes the key and transforms the plaintext into ciphertext. The ciphertext should look like random noise and only by using the same cipher and the same key (or as we will see later in the case of asymmetric ciphers, a mathematically related key) can the plaintext be restored.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The cipher transforms the plaintext's bits using the key's bits. Since we want to be able to decrypt the ciphertext, our cipher needs to be reversible too. We can use [XOR][7] as a simple example. It is reversible and is [its own inverse][8] (P ^ K = C; C ^ K = P) so it can both encrypt plaintext and decrypt ciphertext. A trivial use of an XOR can be used for encryption in a one-time pad, but it is generally not [practical][9]. However, it is possible to combine XOR with a function that generates an arbitrary stream of random data from a single key. Modern ciphers like AES and Chacha20 do exactly that.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

We call any cipher that uses the same key to both encrypt and decrypt a symmetric cipher. Symmetric ciphers are divided into stream ciphers and block ciphers. A stream cipher runs through the message one bit or byte at a time. Our XOR cipher is a stream cipher, for example. Stream ciphers are useful if the length of the plaintext is unknown (such as data coming in from a pipe or socket). [RC4][10] is the best-known stream cipher but it is vulnerable to several different attacks, and the newest version (1.3) of the TLS protocol (the "S" in "HTTPS") does not even support it. [Efforts][11] are underway to create new stream ciphers with some candidates like [ChaCha20][12] already supported in TLS.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

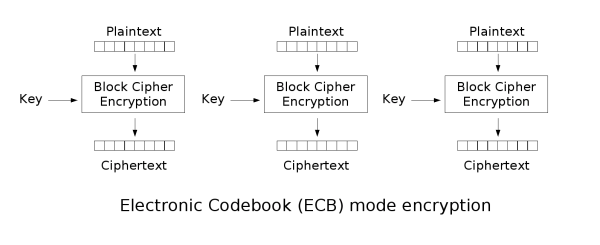

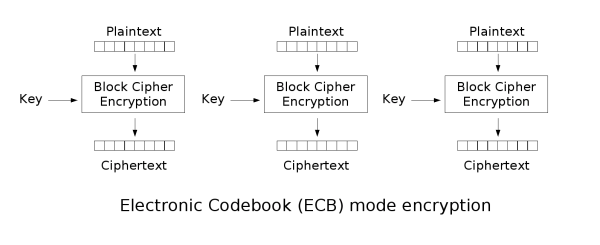

A block cipher takes a fix-sized block and encrypts it with a fixed-sized key. The current king of the hill in the block cipher world is the [Advanced Encryption Standard][13] (AES), and it has a block size of 128 bits. That's not very much data, so block ciphers have a [mode][14] that describes how to apply the cipher's block operation across a message of arbitrary size. The simplest mode is [Electronic Code Book][15] (ECB) which takes the message, splits it into blocks (padding the message's final block if necessary), and then encrypts each block with the key independently.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

You may spot a problem here: if the same block appears multiple times in the message (a phrase like "GET / HTTP/1.1" in web traffic, for example) and we encrypt it using the same key, we'll get the same result. The appearance of a pattern in our encrypted communication makes it vulnerable to attack.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

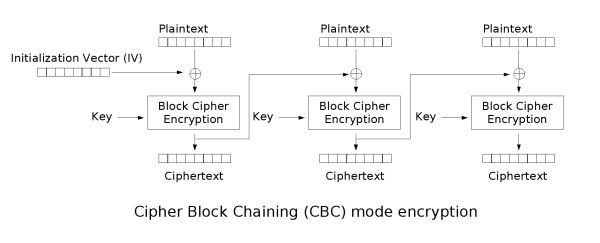

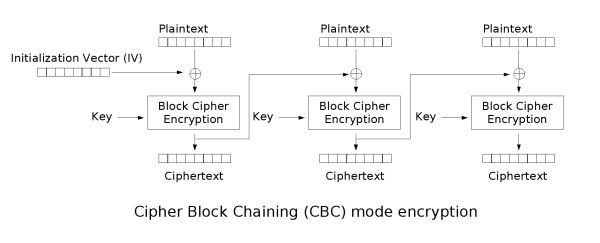

Thus there are more advanced modes such as [Cipher Block Chaining][16] (CBC) where the result of each block's encryption is XORed with the next block's plaintext. The very first block's plaintext is XORed with an initialization vector of random numbers. There are many other modes each with different advantages and disadvantages in security and speed. There are even modes, such as Counter (CTR), that can turn a block cipher into a stream cipher.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

In contrast to symmetric ciphers, there are asymmetric ciphers (also called public-key cryptography). These ciphers use two keys: a public key and a private key. The keys are mathematically related but still distinct. Anything encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the private key and data encrypted with the private key can be decrypted with the public key. The public key is widely distributed while the private key is kept secret. If you want to communicate with a given person, you use their public key to encrypt your message and only their private key can decrypt it. [RSA][17] is the current heavyweight champion of asymmetric ciphers.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

A major downside to asymmetric ciphers is that they are computationally expensive. Can we get authentication with symmetric ciphers to speed things up? If you only share a key with one other person, yes. But that breaks down quickly. Suppose a group of people want to communicate with one another using a symmetric cipher. The group members could establish keys for each unique pairing of members and encrypt messages based on the recipient, but a group of 20 people works out to 190 pairs of members total and 19 keys for each individual to manage and secure. By using an asymmetric cipher, each person only needs to guard their own private key and have access to a listing of public keys.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Asymmetric ciphers are also limited in the [amount of data][18] they can encrypt. Like block ciphers, you have to split a longer message into pieces. In practice then, asymmetric ciphers are often used to establish a confidential, authenticated channel which is then used to exchange a shared key for a symmetric cipher. The symmetric cipher is used for subsequent communications since it is much faster. TLS can operate in exactly this fashion.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### At the foundation

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

At the heart of secure communication are random numbers. Random numbers are used to generate keys and to provide unpredictability for otherwise deterministic processes. If the keys we use are predictable, then we're susceptible to attack right from the very start. Random numbers are difficult to generate on a computer which is meant to behave in a consistent manner. Computers can gather random data from things like mouse movement or keyboard timings. But gathering that randomness (called entropy) takes significant time and involve additional processing to ensure uniform distributions. It can even involve the use of dedicated hardware (such as [a wall of lava lamps][19]). Generally, once we have a truly random value, we use that as a seed to put into a [cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator][20] Beginning with the same seed will always lead to the same stream of numbers, but what's important is that the stream of numbers descended from the seed don't exhibit any pattern. In the Linux kernel, [/dev/random and /dev/urandom][21], operate in this fashion: they gather entropy from multiple sources, process it to remove biases, create a seed, and can then provide the random numbers used to generate an RSA key for example.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Other cryptographic building blocks

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

We've covered confidentiality, but I haven't mentioned integrity or authentication yet. For that, we'll need some new tools in our toolbox.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The first is the cryptographic hash function. A cryptographic hash function is meant to take an input of arbitrary size and produce a fixed size output (often called a digest). If we can find any two messages that create the same digest, that's a collision and makes the hash function unsuitable for cryptography. Note the emphasis on "find"; if we have an infinite world of messages and a fixed sized output, there are bound to be collisions, but if we can find any two messages that collide without a monumental investment of computational resources, that's a deal-breaker. Worse still would be if we could take a specific message and could then find another message that results in a collision.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

As well, the hash function should be one-way: given a digest, it should be computationally infeasible to determine what the message is. Respectively, these [requirements][22] are called collision resistance, second preimage resistance, and preimage resistance. If we meet these requirements, our digest acts as a kind of fingerprint for a message. No two people ([in theory][23]) have the same fingerprints, and you can't take a fingerprint and turn it back into a person.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

If we send a message and a digest, the recipient can use the same hash function to generate an independent digest. If the two digests match, they know the message hasn't been altered. [SHA-256][24] is the most popular cryptographic hash function currently since [SHA-1][25] is starting to [show its age][26].

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Hashes sound great, but what good is sending a digest with a message if someone can tamper with your message and then tamper with the digest too? We need to mix hashing in with the ciphers we have. For symmetric ciphers, we have message authentication codes (MACs). MACs come in different forms, but an HMAC is based on hashing. An [HMAC][27] takes the key K and the message M and blends them together using a hashing function H with the formula H(K + H(K + M)) where "+" is concatenation. Why this formula specifically? That's beyond this article, but it has to do with protecting the integrity of the HMAC itself. The MAC is sent along with an encrypted message. Eve could blindly manipulate the message, but as soon as Bob independently calculates the MAC and compares it to the MAC he received, he'll realize the message has been tampered with.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

For asymmetric ciphers, we have digital signatures. In RSA, encryption with a public key makes something only the private key can decrypt, but the inverse is true as well and can create a type of signature. If only I have the private key and encrypt a document, then only my public key will decrypt the document, and others can implicitly trust that I wrote it: authentication. In fact, we don't even need to encrypt the entire document. If we create a digest of the document, we can then encrypt just the fingerprint. Signing the digest instead of the whole document is faster and solves some problems around the size of a message that can be encrypted using asymmetric encryption. Recipients decrypt the digest, independently calculate the digest for the message, and then compare the two to ensure integrity. The method for digital signatures varies for other asymmetric ciphers, but the concept of using the public key to verify a signature remains.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Putting it all together

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Now that we have all the major pieces, we can implement a [system][28] that has all three of the attributes we're looking for. Alice picks a secret symmetric key and encrypts it with Bob's public key. Then she hashes the resulting ciphertext and uses her private key to sign the digest. Bob receives the ciphertext and the signature, computes the ciphertext's digest and compares it to the digest in the signature he verified using Alice's public key. If the two digests are identical, he knows the symmetric key has integrity and is authenticated. He decrypts the ciphertext with his private key and uses the symmetric key Alice sent him to communicate with her confidentially using HMACs with each message to ensure integrity. There's no protection here against a message being replayed (as seen in the ice cream disaster Eve caused). To handle that issue, we would need some sort of "handshake" that could be used to establish a random, short-lived session identifier.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The cryptographic world is vast and complex, but I hope this article gives you a basic mental model of the core goals and components it uses. With a solid foundation in the concepts, you'll be able to continue learning more.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Thank you to Hubert Kario, Florian Weimer, and Mike Bursell for their help with this article.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/cryptography-pki

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

作者:[Alex Wood][a]

|

|

||||||

选题:[lujun9972](https://github.com/lujun9972)

|

|

||||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

|

||||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/awood

|

|

||||||

[1]:https://security.googleblog.com/2018/02/a-secure-web-is-here-to-stay.html

|

|

||||||

[2]:https://blog.mozilla.org/security/2017/01/20/communicating-the-dangers-of-non-secure-http/

|

|

||||||

[3]:https://letsencrypt.org/

|

|

||||||

[4]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cargo_cult_programming

|

|

||||||

[5]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_and_Bob

|

|

||||||

[6]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_security#Availability

|

|

||||||

[7]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XOR_cipher

|

|

||||||

[8]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Involution_(mathematics)#Computer_science

|

|

||||||

[9]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-time_pad#Problems

|

|

||||||

[10]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RC4

|

|

||||||

[11]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ESTREAM

|

|

||||||

[12]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salsa20

|

|

||||||

[13]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Encryption_Standard

|

|

||||||

[14]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation

|

|

||||||

[15]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation#/media/File:ECB_encryption.svg

|

|

||||||

[16]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation#/media/File:CBC_encryption.svg

|

|

||||||

[17]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RSA_(cryptosystem)

|

|

||||||

[18]:https://security.stackexchange.com/questions/33434/rsa-maximum-bytes-to-encrypt-comparison-to-aes-in-terms-of-security

|

|

||||||

[19]:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cUUfMeOijg

|

|

||||||

[20]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryptographically_secure_pseudorandom_number_generator

|

|

||||||

[21]:https://www.2uo.de/myths-about-urandom/

|

|

||||||

[22]:https://crypto.stackexchange.com/a/1174

|

|

||||||

[23]:https://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/2016/03/14/why-your-fingerprints-may-not-be-unique/

|

|

||||||

[24]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHA-2

|

|

||||||

[25]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHA-1

|

|

||||||

[26]:https://security.googleblog.com/2017/02/announcing-first-sha1-collision.html

|

|

||||||

[27]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAC

|

|

||||||

[28]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hybrid_cryptosystem

|

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,108 @@

|

|||||||

|

密码学及公钥基础设施入门

|

||||||

|

======

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

安全通信正快速成为当今互联网的规范。从 2018 年 7 月起,Google Chrome 将对**全部**使用 HTTP 传输(而不是 HTTPS 传输)的站点[开始显示“不安全”警告][1]。虽然密码学已经逐渐变广为人知,但其本身并没有变得更容易理解。[Let's Encrypt][3] 设计并实现了一套令人惊叹的解决方案,可以提供免费安全证书和周期性续签;但如果不了解底层概念和缺陷,你也不过是加入了类似”[<ruby>船货崇拜<rt>cargo cult</rt></ruby>][4]“的技术崇拜的程序员大军。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 安全通信的特性

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

密码学最直观明显的目标是<ruby>保密性<rt>confidentiality</rt></ruby>:<ruby>消息<rt>message</rt></ruby>传输过程中不会被窥探内容。为了保密性,我们对消息进行加密:对于给定消息,我们结合一个<ruby>密钥<rt>key</rt></ruby>生成一个无意义的乱码,只有通过相同的密钥逆转加密过程(即解密过程)才能将其转换为可读的消息。假设我们有两个朋友 [Alice 和 Bob][5],以及他们的<ruby>八卦<rt>nosy</rt></ruby>邻居 Eve。Alice 加密类似 "Eve 很讨厌" 的消息,将其发送给 Bob,期间不用担心 Eve 会窥探到这条消息的内容。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

对于真正的安全通信,保密性是不够的。假如 Eve 收集了足够多 Alice 和 Bob 之间的消息,发现单词 "Eve" 被加密为 "Xyzzy"。除此之外,Eve 还知道 Alice 和 Bob 正在准备一个派对,Alice 会将访客名单发送给 Bob。如果 Eve 拦截了消息并将 "Xyzzy" 加到访客列表的末尾,那么她已经成功的破坏了这个派对。因此,Alice 和 Bob 需要他们之间的通信可以提供<ruby>完整性<rt>integrity</rt></ruby>:消息应该不会被篡改。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

而且我们还有一个问题有待解决。假如 Eve 观察到 Bob 打开了标记为”来自 Alice“的信封,信封中包含一条来自 Alice 的消息”再买一加仑冰淇淋“。Eve 看到 Bob 外出,回家时带着冰淇淋,这样虽然 Eve 并不知道消息的完整内容,但她对消息有了大致的了解。Bob 将上述消息丢弃,但 Eve 找出了它并在下一周中的每一天都向 Bob 的邮箱中投递一封标记为”来自 Alice“的信封,内容拷贝自之前 Bob 丢弃的那封信。这样到了派对的时候,冰淇淋严重超量;派对当晚结束后,Bob 分发剩余的冰淇淋,Eve 带着免费的冰淇淋回到家。消息是加密的,完整性也没问题,但 Bob 被误导了,没有认出发信人的真实身份。<ruby>身份认证<rt>Authentication</rt></ruby>这个特性用于保证你正在通信的人的确是其声称的那样。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

信息安全还有[其它特性][6],但保密性、完整性和身份验证是你必须了解的三大特性。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 加密和加密算法

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

加密都包含哪些部分呢?首先,需要一条消息,我们称之为<ruby>明文<rt>plaintext</rt></ruby>。接着,需要对明文做一些格式上的初始化,以便用于后续的加密过程(例如,假如我们使用<ruby>分组加密算法<rt>block cipher</rt></ruby>,需要在明文尾部填充使其达到特定长度)。下一步,需要一个保密的比特序列,我们称之为<ruby>密钥<rt>key</rt></ruby>。然后,基于私钥,使用一种加密算法将明文转换为<ruby>密文<rt>ciphertext</rt></ruby>。密文看上去像是随机噪声,只有通过相同的加密算法和相同的密钥(在后面提到的非对称加密算法情况下,是另一个数学上相关的密钥)才能恢复为明文。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

(LCTT 译注:cipher 一般被翻译为密码,但其具体表达的意思是加密算法,这里采用加密算法的翻译)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

加密算法使用密钥加密明文。考虑到希望能够解密密文,我们用到的加密算法也必须是<ruby>可逆的<rt>reversible</rt></ruby>。作为简单示例,我们可以使用 [XOR][7]。该算子可逆,而且逆算子就是本身(P ^ K = C; C ^ K = P),故可同时用于加密和解密。该算子的平凡应用可以是<ruby>一次性密码本<rt>one-time pad</rt></ruby>,但一般而言并不[可行][9]。但可以将 XOR 与一个基于单个密钥生成<ruby>任意随机数据流<rt>arbitrary stream of random data</rt></ruby>的函数结合起来。现代加密算法 AES 和 Chacha20 就是这么设计的。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我们把加密和解密使用同一个密钥的加密算法称为<ruby>对称加密算法<rt>symmetric cipher</rt></ruby>。对称加密算法分为<ruby>流加密算法<rt>stream ciphers</rt></ruby>和分组加密算法两类。流加密算法依次对明文中的每个比特或字节进行加密。例如,我们上面提到的 XOR 加密算法就是一个流加密算法。流加密算法适用于明文长度未知的情形,例如数据从管道或 socket 传入。[RC4][10] 是最为人知的流加密算法,但在多种不同的攻击面前比较脆弱,以至于最新版本 (1.3)的 TLS ("HTTPS" 中的 "S")已经不再支持该加密算法。[Efforts][11] 正着手创建新的加密算法,候选算法 [ChaCha20][12] 已经被 TLS 支持。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

分组加密算法对固定长度的分组,使用固定长度的密钥加密。在分组加密算法领域,排行第一的是 [<ruby>先进加密标准<rt>Advanced Encryption Standard, AES</rt></ruby>][13],使用的分组长度为 128 比特。分组包含的数据并不多,因而分组加密算法包含一个[工作模式][14],用于描述如何对任意长度的明文执行分组加密。最简单的工作模式是 [<ruby>电子密码本<rt>Electronic Code Book, ECB</rt></ruby>][15],将明文按分组大小划分成多个分组(在必要情况下,填充最后一个分组),使用密钥独立的加密各个分组。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

这里我们留意到一个问题:如果相同的分组在明文中出现多次(例如互联网流量中的 "GET / HTTP/1.1" 词组),由于我们使用相同的密钥加密分组,我们会得到相同的加密结果。我们的安全通信中会出现一种<ruby>模式规律<rt>pattern</rt></ruby>,容易受到攻击。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

因此还有很多高级的工作模式,例如 [<ruby>密码分组链接<rt>Cipher Block Chaining, CBC</rt></ruby>][16],其中每个分组的明文在加密前会与前一个分组的密文进行 XOR 操作,而第一个分组的明文与一个随机数构成的初始化向量进行 XOR 操作。还有其它一些工作模式,在安全性和执行速度方面各有优缺点。甚至还有 Counter (CTR) 这种工作模式,可以将分组加密算法转换为流加密算法。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

除了对称加密算法,还有<ruby>非对称加密算法<rt>asymmetric ciphers</rt></ruby>,也被称为<ruby>公钥密码学<rt>public-key cryptography</rt></ruby>。这类加密算法使用两个密钥:一个<ruby>公钥<rt>public key</rt></ruby>,一个<ruby>私钥<rt>private key</rt></ruby>。公钥和私钥在数学上有一定关联,但可以区分二者。经过公钥加密的密文只能通过私钥解密,经过私钥加密的密文可以通过公钥解密。公钥可以大范围分发出去,但私钥必须对外不可见。如果你希望和一个给定的人通信,你可以使用对方的公钥加密消息,这样只有他们的私钥可以解密出消息。在非对称加密算法领域,目前 [RSA][17] 最具有影响力。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

非对称加密算法最主要的缺陷是,它们是<ruby>计算密集型<rt>computationally expensive</rt></ruby>的。那么使用对称加密算法可以让身份验证更快吗?如果你只与一个人共享密钥,答案是肯定的。但这种方式很快就会失效。假如一群人希望使用对称加密算法进行两两通信,如果对每对成员通信都采用单独的密钥,一个 20 人的群体将有 190 对成员通信,即每个成员要维护 19 个密钥并确认其安全性。如果使用非对称加密算法,每个成员仅需确保自己的私钥安全并维护一个公钥列表即可。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

非对称加密算法也有加密[数据长度][18]限制。类似于分组加密算法,你需要将长消息进行划分。但实际应用中,非对称加密算法通常用于建立<ruby>机密<rt>confidential</rt></ruby>、<ruby>已认证<rt>authenticated</rt></ruby>的<ruby>通道<rt>channel</rt></ruby>,利用该通道交换对称加密算法的共享密钥。考虑到速度优势,对称加密算法用于后续的通信。TLS 就是严格按照这种方式运行的。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 基础

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

安全通信的核心在于随机数。随机数用于生成密钥并为<ruby>确定性过程<rt>deterministic processes</rt></ruby>提供不可预测性。如果我们使用的密钥是可预测的,那我们从一开始就可能受到攻击。计算机被设计成按固定规则操作,因此生成随机数是比较困难的。计算机可以收集鼠标移动或<ruby>键盘计时<rt>keyboard timings</rt></ruby>这类随机数据。但收集随机性(也叫<ruby>信息熵<rt>entropy</rt></ruby>)需要花费不少时间,而且涉及额外处理以确保<ruby>均匀分布<rt>uniform distribution</rt></ruby>。甚至可以使用专用硬件,例如[<ruby>熔岩灯<rt>lava lamps</rt></ruby>墙][19]等。一般而言,一旦有了一个真正的随机数值,我们可以将其用作<ruby>种子<rt>seed</rt></ruby>,使用<ruby>密码安全的伪随机数生成器<rt>cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator</rt></ruby>生成随机数。使用相同的种子,同一个随机数生成器生成的随机数序列保持不变,但重要的是随机数序列是无规律的。在 Linux 内核中,[/dev/random 和 /dev/urandom][21] 工作方式如下:从多个来源收集信息熵,进行<ruby>无偏处理<rt>remove biases</rt></ruby>,生成种子,然后生成随机数,该随机数可用于 RSA 密钥生成等。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 其它密码学组件

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我们已经实现了保密性,但还没有考虑完整性和身份验证。对于后两者,我们需要使用一些额外的技术。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

首先是<ruby>密码散列函数<rt>crytographic hash function</rt></ruby>,该函数接受任意长度的输入并给出固定长度的输出(一般称为<ruby>摘要<rt>digest</rt></ruby>)。如果我们找到两条消息,其摘要相同,我们称之为<ruby>碰撞<rt>collision</rt></ruby>,对应的散列函数就不适合用于密码学。这里需要强调一下“找到”:考虑到消息的条数是无限的而摘要的长度是固定的,那么总是会存在碰撞;但如果无需海量的计算资源,我们总是能找到发生碰撞的消息对,那就令人比较担心了。更严重的情况是,对于每一个给定的消息,都能找到与之碰撞的另一条消息。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

另外,哈希函数必须是<ruby>单向的<rt>one-way</rt></ruby>:给定一个摘要,反向计算对应的消息在计算上不可行。相应的,这类[条件][22]被称为<ruby>碰撞阻力<rt>collision resistance</rt></ruby>、<ruby>第二原象抗性<rt>second preimage resistance</rt></ruby>和<ruby>原象抗性<rt>preimage resistance</rt></ruby>。如果满足这些条件,摘要可以用作消息的指纹。[理论上][23]不存在具有相同指纹的两个人,而且你无法使用指纹反向找到其对应的人。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

如果我们同时发送消息及其摘要,接收者可以使用相同的哈希函数独立计算摘要。如果两个摘要相同,可以认为消息没有被篡改。考虑到 [SHA-1][25] 已经变得[有些过时][26],目前最流行的密码散列函数是 [SHA-256][24]。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

散列函数看起来不错,但如果有人可以同时篡改消息及其摘要,那么消息发送仍然是不安全的。我们需要将哈希与加密算法结合起来。在对称加密算法领域,我们有<ruby>消息认证码<rt>message authentication codes, MACs</rt></ruby>技术。MACs 有多种形式,但<ruby>哈希消息认证码<rt>hash message authentication codes, HMAC</rt></ruby> 这类是基于哈希的。[HMAC][27] 使用哈希函数 H 处理密钥 K、消息 M,公式为 H(K + H(K + M)),其中 "+" 代表<ruby>连接<rt>concatenation</rt></ruby>。公式的独特之处并不在本文讨论范围内,大致来说与保护 HMAC 自身的完整性有关。发送加密消息的同时也发送 MAC。Eve 可以任意篡改消息,但一旦 Bob 独立计算 MAC 并与接收到的 MAC 做比较,就会发现消息已经被篡改。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在非对称加密算法领域,我们有<ruby>数字签名<rt>digital signatures</rt></ruby>技术。如果使用 RSA,使用公钥加密的内容只能通过私钥解密,反过来也是如此;这种机制可用于创建一种签名。如果只有我持有私钥并用其加密文档,那么只有我的公钥可以用于解密,那么大家潜在的承认文档是我写的:这是一种身份验证。事实上,我们无需加密整个文档。如果生成文档的摘要,只要对这个指纹加密即可。对摘要签名比对整个文档签名要快得多,而且可以解决非对称加密存在的消息长度限制问题。接收者解密出摘要信息,独立计算消息的摘要并进行比对,可以确保消息的完整性。对于不同的非对称加密算法,数字签名的方法也各不相同;但核心都是使用公钥来检验已有签名。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 汇总

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

现在,我们已经有了全部的主体组件,可以用其实现一个我们期待的、具有全部三个特性的[<ruby>体系<rt>system</rt></ruby>][28]。Alice 选取一个保密的对称加密密钥并使用 Bob 的公钥进行加密。接着,她对得到的密文进行哈希并使用其私钥对摘要进行签名。Bob 接收到密文和签名,一方面独立计算密文的摘要,另一方面使用 Alice 的公钥解密签名中的摘要;如果两个摘要相同,他可以确信对称加密密钥没有被篡改且通过了身份验证。Bob 使用私钥解密密文得到对称加密密钥,接着使用该密钥及 HMAC 与 Alice 进行保密通信,这样每一条消息的完整性都得到保障。但该体系没有办法抵御消息重放攻击(我们在 Eve 造成的冰淇淋灾难中见过这种攻击)。要解决重放攻击,我们需要使用某种类型的“<ruby>握手<rt>handshake</rt></ruby>”建立随机、短期的<ruby>会话标识符<rt>session identifier</rt></ruby>。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

密码学的世界博大精深,我希望这篇文章能让你对密码学的核心目标及其组件有一个大致的了解。这些概念为你打下坚实的基础,让你可以继续深入学习。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

感谢 Hubert Kario,Florian Weimer 和 Mike Bursell 在本文写作过程中提供的帮助。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/cryptography-pki

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

作者:[Alex Wood][a]

|

||||||

|

选题:[lujun9972](https://github.com/lujun9972)

|

||||||

|

译者:[pinewall](https://github.com/pinewall)

|

||||||

|

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/awood

|

||||||

|

[1]:https://security.googleblog.com/2018/02/a-secure-web-is-here-to-stay.html

|

||||||

|

[2]:https://blog.mozilla.org/security/2017/01/20/communicating-the-dangers-of-non-secure-http/

|

||||||

|

[3]:https://letsencrypt.org/

|

||||||

|

[4]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cargo_cult_programming

|

||||||

|

[5]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_and_Bob

|

||||||

|

[6]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_security#Availability

|

||||||

|

[7]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XOR_cipher

|

||||||

|

[8]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Involution_(mathematics)#Computer_science

|

||||||

|

[9]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-time_pad#Problems

|

||||||

|

[10]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RC4

|

||||||

|

[11]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ESTREAM

|

||||||

|

[12]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salsa20

|

||||||

|

[13]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Encryption_Standard

|

||||||

|

[14]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation

|

||||||

|

[15]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation#/media/File:ECB_encryption.svg

|

||||||

|

[16]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_cipher_mode_of_operation#/media/File:CBC_encryption.svg

|

||||||

|

[17]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RSA_(cryptosystem)

|

||||||

|

[18]:https://security.stackexchange.com/questions/33434/rsa-maximum-bytes-to-encrypt-comparison-to-aes-in-terms-of-security

|

||||||

|

[19]:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cUUfMeOijg

|

||||||

|

[20]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryptographically_secure_pseudorandom_number_generator

|

||||||

|

[21]:https://www.2uo.de/myths-about-urandom/

|

||||||

|

[22]:https://crypto.stackexchange.com/a/1174

|

||||||

|

[23]:https://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/2016/03/14/why-your-fingerprints-may-not-be-unique/

|

||||||

|

[24]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHA-2

|

||||||

|

[25]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHA-1

|

||||||

|

[26]:https://security.googleblog.com/2017/02/announcing-first-sha1-collision.html

|

||||||

|

[27]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAC

|

||||||

|

[28]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hybrid_cryptosystem

|

||||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user