mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-22 23:00:57 +08:00

364 lines

15 KiB

Markdown

364 lines

15 KiB

Markdown

|

|

translating by lujun9972

|

||

|

|

Advanced Python Debugging with pdb

|

||

|

|

======

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Python's built-in [`pdb`][1] module is extremely useful for interactive debugging, but has a bit of a learning curve. For a long time, I stuck to basic `print`-debugging and used `pdb` on a limited basis, which meant I missed out on a lot of features that would have made debugging faster and easier.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

In this post I will show you a few tips I've picked up over the years to level up my interactive debugging skills.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Print debugging vs. interactive debugging

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

First, why would you want to use an interactive debugger instead of inserting `print` or `logging` statements into your code?

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

With `pdb`, you have a lot more flexibility to run, resume, and alter the execution of your program without touching the underlying source. Once you get good at this, it means more time spent diving into issues and less time context switching back and forth between your editor and the command line.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Also, by not touching the underlying source code, you will have the ability to step into third party code (e.g. modules installed from PyPI) and the standard library.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Post-mortem debugging

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

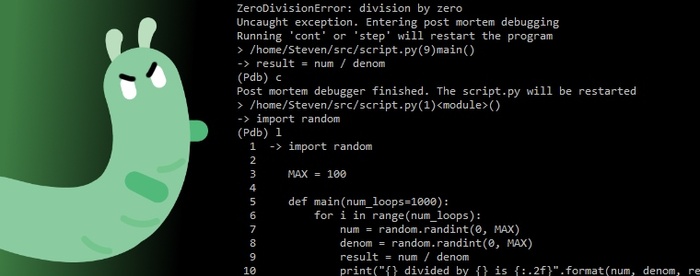

The first workflow I used after moving away from `print` debugging was `pdb`'s "post-mortem debugging" mode. This is where you run your program as usual, but whenever an unhandled exception is thrown, you drop down into the debugger to poke around in the program state. After that, you attempt to make a fix and repeat the process until the problem is resolved.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

You can run an existing script with the post-mortem debugger by using Python's `-mpdb` option:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

python3 -mpdb path/to/script.py

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

From here, you are dropped into a `(Pdb)` prompt. To start execution, you use the `continue` or `c` command. If the program executes successfully, you will be taken back to the `(Pdb)` prompt where you can restart the execution again. At this point, you can use `quit` / `q` or Ctrl+D to exit the debugger.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

If the program throws an unhandled exception, you'll also see a `(Pdb)` prompt, but with the program execution stopped at the line that threw the exception. From here, you can run Python code and debugger commands at the prompt to inspect the current program state.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Testing our basic workflow

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

To see how these basic debugging steps work, I'll be using this (buggy) program:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

import random

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

MAX = 100

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

def main(num_loops=1000):

|

||

|

|

for i in range(num_loops):

|

||

|

|

num = random.randint(0, MAX)

|

||

|

|

denom = random.randint(0, MAX)

|

||

|

|

result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

print("{} divided by {} is {:.2f}".format(num, denom, result))

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

if __name__ == "__main__":

|

||

|

|

import sys

|

||

|

|

arg = sys.argv[-1]

|

||

|

|

if arg.isdigit():

|

||

|

|

main(arg)

|

||

|

|

else:

|

||

|

|

main()

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

We're expecting the program to do some basic math operations on random numbers in a loop and print the result. Try running it normally and you will see one of the bugs:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

$ python3 script.py

|

||

|

|

2 divided by 30 is 0.07

|

||

|

|

65 divided by 41 is 1.59

|

||

|

|

0 divided by 70 is 0.00

|

||

|

|

...

|

||

|

|

38 divided by 26 is 1.46

|

||

|

|

Traceback (most recent call last):

|

||

|

|

File "script.py", line 16, in <module>

|

||

|

|

main()

|

||

|

|

File "script.py", line 7, in main

|

||

|

|

result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Let's try post-mortem debugging this error:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

$ python3 -mpdb script.py

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(1)<module>()

|

||

|

|

-> import random

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) c

|

||

|

|

49 divided by 46 is 1.07

|

||

|

|

...

|

||

|

|

Traceback (most recent call last):

|

||

|

|

File "/usr/lib/python3.4/pdb.py", line 1661, in main

|

||

|

|

pdb._runscript(mainpyfile)

|

||

|

|

File "/usr/lib/python3.4/pdb.py", line 1542, in _runscript

|

||

|

|

self.run(statement)

|

||

|

|

File "/usr/lib/python3.4/bdb.py", line 431, in run

|

||

|

|

exec(cmd, globals, locals)

|

||

|

|

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

|

||

|

|

File "./src/script.py", line 1, in <module>

|

||

|

|

import random

|

||

|

|

File "./src/script.py", line 7, in main

|

||

|

|

result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

|

||

|

|

Uncaught exception. Entering post mortem debugging

|

||

|

|

Running 'cont' or 'step' will restart the program

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(7)main()

|

||

|

|

-> result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) num

|

||

|

|

76

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) denom

|

||

|

|

0

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) random.randint(0, MAX)

|

||

|

|

56

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) random.randint(0, MAX)

|

||

|

|

79

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) random.randint(0, 1)

|

||

|

|

0

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) random.randint(1, 1)

|

||

|

|

1

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Once the post-mortem debugger kicks in, we can inspect all of the variables in the current frame and even run new code to help us figure out what's wrong and attempt to make a fix.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Dropping into the debugger from Python code using `pdb.set_trace`

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Another technique that I used early on, after starting to use `pdb`, was forcing the debugger to run at a certain line of code before an error occurred. This is a common next step after learning post-mortem debugging because it feels similar to debugging with `print` statements.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

For example, in the above code, if we want to stop execution before the division operation, we could add a `pdb.set_trace` call to our program here:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

import pdb; pdb.set_trace()

|

||

|

|

result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

And then run our program without `-mpdb`:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

$ python3 script.py

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(10)main()

|

||

|

|

-> result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) num

|

||

|

|

94

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) denom

|

||

|

|

19

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

The problem with this method is that you have to constantly drop these statements into your source code, remember to remove them afterwards, and switch between running your code with `python` vs. `python -mpdb`.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Using `pdb.set_trace` gets the job done, but **breakpoints** are an even more flexible way to stop the debugger at any line (even third party or standard library code), without needing to modify any source code. Let's learn about breakpoints and a few other useful commands.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Debugger commands

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

There are over 30 commands you can give to the interactive debugger, a list that can be seen by using the `help` command when at the `(Pdb)` prompt:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) help

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Documented commands (type help <topic>):

|

||

|

|

========================================

|

||

|

|

EOF c d h list q rv undisplay

|

||

|

|

a cl debug help ll quit s unt

|

||

|

|

alias clear disable ignore longlist r source until

|

||

|

|

args commands display interact n restart step up

|

||

|

|

b condition down j next return tbreak w

|

||

|

|

break cont enable jump p retval u whatis

|

||

|

|

bt continue exit l pp run unalias where

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

You can use `help <topic>` for more information on a given command.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Instead of walking through each command, I'll list out the ones I've found most useful and what arguments they take.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

**Setting breakpoints** :

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* `l(ist)`: displays the source code of the currently running program, with line numbers, for the 10 lines around the current statement.

|

||

|

|

* `l 1,999`: displays the source code of lines 1-999. I regularly use this to see the source for the entire program. If your program only has 20 lines, it'll just show all 20 lines.

|

||

|

|

* `b(reakpoint)`: displays a list of current breakpoints.

|

||

|

|

* `b 10`: set a breakpoint at line 10. Breakpoints are referred to by a numeric ID, starting at 1.

|

||

|

|

* `b main`: set a breakpoint at the function named `main`. The function name must be in the current scope. You can also set breakpoints on functions in other modules in the current scope, e.g. `b random.randint`.

|

||

|

|

* `b script.py:10`: sets a breakpoint at line 10 in `script.py`. This gives you another way to set breakpoints in another module.

|

||

|

|

* `clear`: clears all breakpoints.

|

||

|

|

* `clear 1`: clear breakpoint 1.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

**Stepping through execution** :

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* `c(ontinue)`: execute until the program finishes, an exception is thrown, or a breakpoint is hit.

|

||

|

|

* `s(tep)`: execute the next line, whatever it is (your code, stdlib, third party code, etc.). Use this when you want to step down into function calls you're interested in.

|

||

|

|

* `n(ext)`: execute the next line in the current function (will not step into downstream function calls). Use this when you're only interested in the current function.

|

||

|

|

* `r(eturn)`: execute the remaining lines in the current function until it returns. Use this to skip over the rest of the function and go up a level. For example, if you've stepped down into a function by mistake.

|

||

|

|

* `unt(il) [lineno]`: execute until the current line exceeds the current line number. This is useful when you've stepped into a loop but want to let the loop continue executing without having to manually step through every iteration. Without any argument, this command behaves like `next` (with the loop skipping behavior, once you've stepped through the loop body once).

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

**Moving up and down the stack** :

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* `w(here)`: shows an annotated view of the stack trace, with your current frame marked by `>`.

|

||

|

|

* `u(p)`: move up one frame in the current stack trace. For example, when post-mortem debugging, you'll start off on the lowest level of the stack and typically want to move `up` a few times to help figure out what went wrong.

|

||

|

|

* `d(own)`: move down one frame in the current stack trace.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

**Additional commands and tips** :

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* `pp <expression>`: This will "pretty print" the result of the given expression using the [`pprint`][2] module. Example:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) stuff = "testing the pp command in pdb with a big list of strings"

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) pp [(i, x) for (i, x) in enumerate(stuff.split())]

|

||

|

|

[(0, 'testing'),

|

||

|

|

(1, 'the'),

|

||

|

|

(2, 'pp'),

|

||

|

|

(3, 'command'),

|

||

|

|

(4, 'in'),

|

||

|

|

(5, 'pdb'),

|

||

|

|

(6, 'with'),

|

||

|

|

(7, 'a'),

|

||

|

|

(8, 'big'),

|

||

|

|

(9, 'list'),

|

||

|

|

(10, 'of'),

|

||

|

|

(11, 'strings')]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* `!<python code>`: sometimes the Python code you run in the debugger will be confused for a command. For example `c = 1` will trigger the `continue` command. To force the debugger to execute Python code, prefix the line with `!`, e.g. `!c = 1`.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* Pressing the Enter key at the `(Pdb)` prompt will execute the previous command again. This is most useful after the `s`/`n`/`r`/`unt` commands to quickly step through execution line-by-line.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* You can run multiple commands on one line by separating them with `;;`, e.g. `b 8 ;; c`.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* The `pdb` module can take multiple `-c` arguments on the command line to execute commands as soon as the debugger starts.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Example:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

python3 -mpdb -cc script.py # run the program without you having to enter an initial "c" at the prompt

|

||

|

|

python3 -mpdb -c "b 8" -cc script.py # sets a breakpoint on line 8 and runs the program

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Restart behavior

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Another thing that can shave time off debugging is understanding how `pdb`'s restart behavior works. You may have noticed that after execution stops, `pdb` will give a message like, "The program finished and will be restarted," or "The script will be restarted." When I first started using `pdb`, I would always quit and re-run `python -mpdb ...` to make sure that my code changes were getting picked up, which was unnecessary in most cases.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

When `pdb` says it will restart the program, or when you use the `restart` command, code changes to the script you're debugging will be reloaded automatically. Breakpoints will still be set after reloading, but may need to be cleared and re-set due to line numbers shifting. Code changes to other imported modules will not be reloaded -- you will need to `quit` and re-run the `-mpdb` command to pick those up.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Watches

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

One feature you may miss from other interactive debuggers is the ability to "watch" a variable change throughout the program's execution. `pdb` does not include a watch command by default, but you can get something similar by using `commands`, which lets you run arbitrary Python code whenever a breakpoint is hit.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

To watch what happens to the `denom` variable in our example program:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

$ python3 -mpdb script.py

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(1)<module>()

|

||

|

|

-> import random

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) b 9

|

||

|

|

Breakpoint 1 at ./src/script.py:9

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) commands

|

||

|

|

(com) silent

|

||

|

|

(com) print("DENOM: {}".format(denom))

|

||

|

|

(com) c

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) c

|

||

|

|

DENOM: 77

|

||

|

|

71 divided by 77 is 0.92

|

||

|

|

DENOM: 27

|

||

|

|

100 divided by 27 is 3.70

|

||

|

|

DENOM: 10

|

||

|

|

82 divided by 10 is 8.20

|

||

|

|

DENOM: 20

|

||

|

|

...

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

We first set a breakpoint (which is assigned ID 1), then use `commands` to start entering a block of commands. These commands function as if you had typed them at the `(Pdb)` prompt. They can be either Python code or additional `pdb` commands.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Once we start the `commands` block, the prompt changes to `(com)`. The `silent` command means the following commands will not be echoed back to the screen every time they're executed, which makes reading the output a little easier.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

After that, we run a `print` statement to inspect the variable, similar to what we might do when `print` debugging. Finally, we end with a `c` to continue execution, which ends the command block. Typing `c` again at the `(Pdb)` prompt starts execution and we see our new `print` statement running.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

If you'd rather stop execution instead of continuing, you can use `end` instead of `c` in the command block.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Running pdb from the interpreter

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Another way to run `pdb` is via the interpreter, which is useful when you're experimenting interactively and would like to drop into `pdb` without running a standalone script.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

For post-mortem debugging, all you need is a call to `pdb.pm()` after an exception has occurred:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

$ python3

|

||

|

|

>>> import script

|

||

|

|

>>> script.main()

|

||

|

|

17 divided by 60 is 0.28

|

||

|

|

...

|

||

|

|

56 divided by 94 is 0.60

|

||

|

|

Traceback (most recent call last):

|

||

|

|

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

|

||

|

|

File "./src/script.py", line 9, in main

|

||

|

|

result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

|

||

|

|

>>> import pdb

|

||

|

|

>>> pdb.pm()

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(9)main()

|

||

|

|

-> result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) num

|

||

|

|

4

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) denom

|

||

|

|

0

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

If you want to step through normal execution instead, use the `pdb.run()` function:

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

$ python3

|

||

|

|

>>> import script

|

||

|

|

>>> import pdb

|

||

|

|

>>> pdb.run("script.main()")

|

||

|

|

> <string>(1)<module>()

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) b script:6

|

||

|

|

Breakpoint 1 at ./src/script.py:6

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) c

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(6)main()

|

||

|

|

-> for i in range(num_loops):

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) n

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(7)main()

|

||

|

|

-> num = random.randint(0, MAX)

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) n

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(8)main()

|

||

|

|

-> denom = random.randint(0, MAX)

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) n

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(9)main()

|

||

|

|

-> result = num / denom

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) n

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(10)main()

|

||

|

|

-> print("{} divided by {} is {:.2f}".format(num, denom, result))

|

||

|

|

(Pdb) n

|

||

|

|

66 divided by 70 is 0.94

|

||

|

|

> ./src/script.py(6)main()

|

||

|

|

-> for i in range(num_loops):

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

This one is a little trickier than `-mpdb` because you don't have the ability to step through an entire program. Instead, you'll need to manually set a breakpoint, e.g. on the first statement of the function you're trying to execute.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

## Conclusion

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Hopefully these tips have given you a few new ideas on how to use `pdb` more effectively. After getting a handle on these, you should be able to pick up the [other commands][3] and start customizing `pdb` via a `.pdbrc` file ([example][4]).

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

You can also look into other front-ends for debugging, like [pdbpp][5], [pudb][6], and [ipdb][7], or GUI debuggers like the one included in PyCharm. Happy debugging!

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

via: https://www.codementor.io/stevek/advanced-python-debugging-with-pdb-g56gvmpfa

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

作者:[Steven Kryskalla][a]

|

||

|

|

译者:[lujun9972](https://github.com/lujun9972)

|

||

|

|

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[a]:https://www.codementor.io/stevek

|

||

|

|

[1]:https://docs.python.org/3/library/pdb.html

|

||

|

|

[2]:https://docs.python.org/3/library/pprint.html

|

||

|

|

[3]:https://docs.python.org/3/library/pdb.html#debugger-commands

|

||

|

|

[4]:https://nedbatchelder.com/blog/200704/my_pdbrc.html

|

||

|

|

[5]:https://pypi.python.org/pypi/pdbpp/

|

||

|

|

[6]:https://pypi.python.org/pypi/pudb/

|

||

|

|

[7]:https://pypi.python.org/pypi/ipdb

|