mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-19 22:51:41 +08:00

163 lines

8.4 KiB

Markdown

163 lines

8.4 KiB

Markdown

|

|

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

|

|||

|

|

[#]: translator: ( )

|

|||

|

|

[#]: reviewer: ( )

|

|||

|

|

[#]: publisher: ( )

|

|||

|

|

[#]: url: ( )

|

|||

|

|

[#]: subject: (How to add a player to your Python game)

|

|||

|

|

[#]: via: (https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-add-a-player)

|

|||

|

|

[#]: author: (Seth Kenlon https://opensource.com/users/seth)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

How to add a player to your Python game

|

|||

|

|

======

|

|||

|

|

Part three of a series on building a game from scratch with Python.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In the [first article of this series][1], I explained how to use Python to create a simple, text-based dice game. In the second part, I showed you how to build a game from scratch, starting with [creating the game's environment][2]. But every game needs a player, and every player needs a playable character, so that's what we'll do next in the third part of the series.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In Pygame, the icon or avatar that a player controls is called a sprite. If you don't have any graphics to use for a player sprite yet, create something for yourself using [Krita][3] or [Inkscape][4]. If you lack confidence in your artistic skills, you can also search [OpenClipArt.org][5] or [OpenGameArt.org][6] for something pre-generated. Then, if you didn't already do so in the previous article, create a directory called `images` alongside your Python project directory. Put the images you want to use in your game into the `images` folder.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

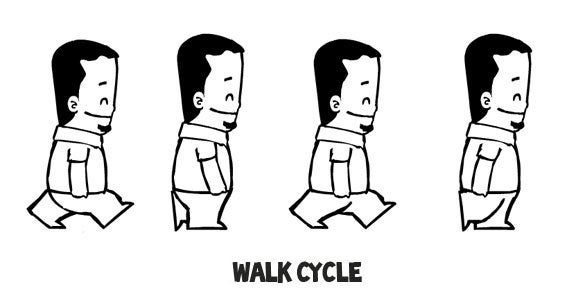

To make your game truly exciting, you ought to use an animated sprite for your hero. It means you have to draw more assets, but it makes a big difference. The most common animation is a walk cycle, a series of drawings that make it look like your sprite is walking. The quick and dirty version of a walk cycle requires four drawings.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Note: The code samples in this article allow for both a static player sprite and an animated one.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Name your player sprite `hero.png`. If you're creating an animated sprite, append a digit after the name, starting with `hero1.png`.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Create a Python class

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In Python, when you create an object that you want to appear on screen, you create a class.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Near the top of your Python script, add the code to create a player. In the code sample below, the first three lines are already in the Python script that you're working on:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

import pygame

|

|||

|

|

import sys

|

|||

|

|

import os # new code below

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

class Player(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

|

|||

|

|

'''

|

|||

|

|

Spawn a player

|

|||

|

|

'''

|

|||

|

|

def __init__(self):

|

|||

|

|

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

|

|||

|

|

self.images = []

|

|||

|

|

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero.png')).convert()

|

|||

|

|

self.images.append(img)

|

|||

|

|

self.image = self.images[0]

|

|||

|

|

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

If you have a walk cycle for your playable character, save each drawing as an individual file called `hero1.png` to `hero4.png` in the `images` folder.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Use a loop to tell Python to cycle through each file.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

'''

|

|||

|

|

Objects

|

|||

|

|

'''

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

class Player(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

|

|||

|

|

'''

|

|||

|

|

Spawn a player

|

|||

|

|

'''

|

|||

|

|

def __init__(self):

|

|||

|

|

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

|

|||

|

|

self.images = []

|

|||

|

|

for i in range(1,5):

|

|||

|

|

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero' + str(i) + '.png')).convert()

|

|||

|

|

self.images.append(img)

|

|||

|

|

self.image = self.images[0]

|

|||

|

|

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Bring the player into the game world

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Now that a Player class exists, you must use it to spawn a player sprite in your game world. If you never call on the Player class, it never runs, and there will be no player. You can test this out by running your game now. The game will run just as well as it did at the end of the previous article, with the exact same results: an empty game world.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

To bring a player sprite into your world, you must call the Player class to generate a sprite and then add it to a Pygame sprite group. In this code sample, the first three lines are existing code, so add the lines afterwards:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

world = pygame.display.set_mode([worldx,worldy])

|

|||

|

|

backdrop = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','stage.png')).convert()

|

|||

|

|

backdropbox = screen.get_rect()

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# new code below

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

player = Player() # spawn player

|

|||

|

|

player.rect.x = 0 # go to x

|

|||

|

|

player.rect.y = 0 # go to y

|

|||

|

|

player_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

|

|||

|

|

player_list.add(player)

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Try launching your game to see what happens. Warning: it won't do what you expect. When you launch your project, the player sprite doesn't spawn. Actually, it spawns, but only for a millisecond. How do you fix something that only happens for a millisecond? You might recall from the previous article that you need to add something to the main loop. To make the player spawn for longer than a millisecond, tell Python to draw it once per loop.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Change the bottom clause of your loop to look like this:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

world.blit(backdrop, backdropbox)

|

|||

|

|

player_list.draw(screen) # draw player

|

|||

|

|

pygame.display.flip()

|

|||

|

|

clock.tick(fps)

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Launch your game now. Your player spawns!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Setting the alpha channel

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Depending on how you created your player sprite, it may have a colored block around it. What you are seeing is the space that ought to be occupied by an alpha channel. It's meant to be the "color" of invisibility, but Python doesn't know to make it invisible yet. What you are seeing, then, is the space within the bounding box (or "hit box," in modern gaming terms) around the sprite.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

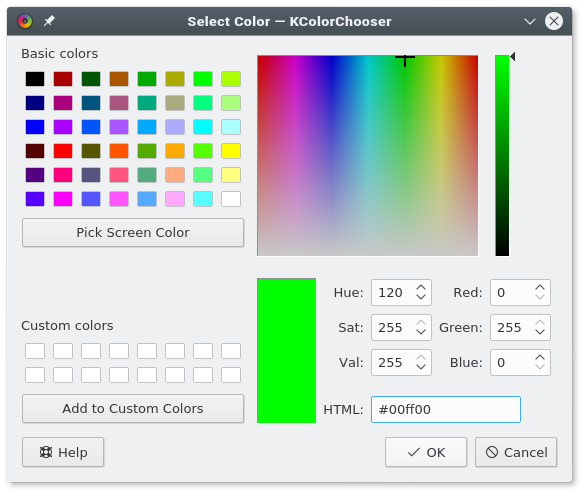

You can tell Python what color to make invisible by setting an alpha channel and using RGB values. If you don't know the RGB values your drawing uses as alpha, open your drawing in Krita or Inkscape and fill the empty space around your drawing with a unique color, like #00ff00 (more or less a "greenscreen green"). Take note of the color's hex value (#00ff00, for greenscreen green) and use that in your Python script as the alpha channel.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Using alpha requires the addition of two lines in your Sprite creation code. Some version of the first line is already in your code. Add the other two lines:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero' + str(i) + '.png')).convert()

|

|||

|

|

img.convert_alpha() # optimise alpha

|

|||

|

|

img.set_colorkey(ALPHA) # set alpha

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Python doesn't know what to use as alpha unless you tell it. In the setup area of your code, add some more color definitions. Add this variable definition anywhere in your setup section:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

ALPHA = (0, 255, 0)

|

|||

|

|

```

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In this example code, **0,255,0** is used, which is the same value in RGB as #00ff00 is in hex. You can get all of these color values from a good graphics application like [GIMP][7], Krita, or Inkscape. Alternately, you can also detect color values with a good system-wide color chooser, like [KColorChooser][8].

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

If your graphics application is rendering your sprite's background as some other value, adjust the values of your alpha variable as needed. No matter what you set your alpha value, it will be made "invisible." RGB values are very strict, so if you need to use 000 for alpha, but you need 000 for the black lines of your drawing, just change the lines of your drawing to 111, which is close enough to black that nobody but a computer can tell the difference.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Launch your game to see the results.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In the [fourth part of this series][9], I'll show you how to make your sprite move. How exciting!

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-add-a-player

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

作者:[Seth Kenlon][a]

|

|||

|

|

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

|||

|

|

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

|||

|

|

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

[a]: https://opensource.com/users/seth

|

|||

|

|

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

|||

|

|

[1]: https://opensource.com/article/17/10/python-101

|

|||

|

|

[2]: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/program-game-python-part-2-creating-game-world

|

|||

|

|

[3]: http://krita.org

|

|||

|

|

[4]: http://inkscape.org

|

|||

|

|

[5]: http://openclipart.org

|

|||

|

|

[6]: https://opengameart.org/

|

|||

|

|

[7]: http://gimp.org

|

|||

|

|

[8]: https://github.com/KDE/kcolorchooser

|

|||

|

|

[9]: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/program-game-python-part-4-moving-your-sprite

|