mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-19 22:51:41 +08:00

312 lines

12 KiB

Markdown

312 lines

12 KiB

Markdown

|

|

How to turn your CentOS box into a BGP router using Quagga

|

|||

|

|

================================================================================

|

|||

|

|

In a [previous tutorial][1](注:此文原文做过,文件名:“20140928 How to turn your CentOS box into an OSPF router using Quagga.md”,如果前面翻译发布了,可以修改此链接), I described how we can easily turn a Linux box into a fully-fledged OPSF router using Quagga, an open source routing software suite. In this tutorial, I will focus on **converting a Linux box into a BGP router, again using Quagga**, and demonstrate how to set up BGP peering with other BGP routers.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Before we get into details, a little background on BGP may be useful. Border Gateway Protocol (or BGP) is the de-facto standard inter-domain routing protocol of the Internet. In BGP terminology, the global Internet is a collection of tens of thousands of interconnected Autonomous Systems (ASes), where each AS represents an administrative domain of networks managed by a particular provider.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

To make its networks globally routable, each AS needs to know how to reach all other ASes in the Internet. That is when BGP comes into play. BGP is the language used by an AS to exchange route information with other neighboring ASes. The route information, often called BGP routes or BGP prefixes, contains AS number (ASN; a globally unique number) and its associated IP address block(s). Once all BGP routes are learned and populated in local BGP routing tables, each AS will know how to reach any public IP addresses on the Internet.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The ability to route across different domains (ASes) is the primary reason why BGP is called an Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP) or inter-domain protocol. Whereas routing protocols such as OSPF, IS-IS, RIP and EIGRP are all Interior Gateway Protocols (IGPs) or intra-domain routing protocols.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Test Scenarios ###

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

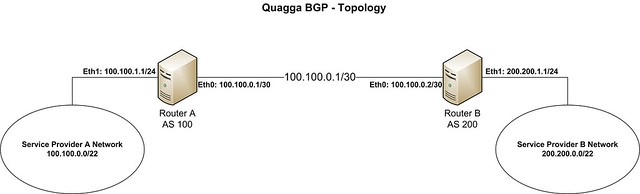

For this tutorial, let us consider the following topology.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

We assume that service provider A wants to establish a BGP peering with service provider B to exchange routes. The details of their AS and IP address spaces are like the following.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

- **Service provider A**: ASN (100), IP address space (100.100.0.0/22), IP address assigned to eth1 of a BGP router (100.100.1.1)

|

|||

|

|

- **Service provider B**: ASN (200), IP address space (200.200.0.0/22), IP address assigned to eth1 of a BGP router (200.200.1.1)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router A and router B will be using the 100.100.0.0/30 subnet for connecting to each other. In theory, any subnet reachable from both service providers can be used for interconnection. In real life, it is advisable to use a /30 subnet from service provider A or service provider B's public IP address space.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Installing Quagga on CentOS ###

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

If Quagga is not already installed, we install Quagga using yum.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# yum install quagga

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

If you are using CentOS 7, you need to apply the following policy change for SELinux. Otherwise, SELinux will prevent Zebra daemon from writing to its configuration directory. You can skip this step if you are using CentOS 6.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# setsebool -P zebra_write_config 1

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The Quagga software suite contains several daemons that work together. For BGP routing, we will focus on setting up the following two daemons.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

- **Zebra**: a core daemon responsible for kernel interfaces and static routes.

|

|||

|

|

- **BGPd**: a BGP daemon.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Configuring Logging ###

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

After Quagga is installed, the next step is to configure Zebra to manage network interfaces of BGP routers. We start by creating a Zebra configuration file and enabling logging.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# cp /usr/share/doc/quagga-XXXXX/zebra.conf.sample /etc/quagga/zebra.conf

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

On CentOS 6:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# service zebra start

|

|||

|

|

# chkconfig zebra on

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

For CentOS 7:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# systemctl start zebra

|

|||

|

|

# systemctl enable zebra

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Quagga offers a dedicated command-line shell called vtysh, where you can type commands which are compatible with those supported by router vendors such as Cisco and Juniper. We will be using vtysh shell to configure BGP routers in the rest of the tutorial.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

To launch vtysh command shell, type:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# vtysh

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The prompt will be changed to hostname, which indicates that you are inside vtysh shell.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A#

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Now we specify the log file for Zebra by using the following commands:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# configure terminal

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# log file /var/log/quagga/quagga.log

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# exit

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Save Zebra configuration permanently:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# write

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Repeat this process on Router-B as well.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Configuring Peering IP Addresses ###

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Next, we configure peering IP addresses on available interfaces.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show interface

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Interface eth0 is up, line protocol detection is disabled

|

|||

|

|

. . . . .

|

|||

|

|

Interface eth1 is up, line protocol detection is disabled

|

|||

|

|

. . . . .

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Configure eth0 interface's parameters:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR# configure terminal

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config)# interface eth0

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# ip address 100.100.0.1/30

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# description "to Router-B"

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# no shutdown

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# exit

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Go ahead and configure eth1 interface's parameters:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config)# interface eth1

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# ip address 100.100.1.1/24

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# description "test ip from provider A network"

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# no shutdown

|

|||

|

|

site-A-RTR(config-if)# exit

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Now verify configuration:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show interface

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Interface eth0 is up, line protocol detection is disabled

|

|||

|

|

Description: "to Router-B"

|

|||

|

|

inet 100.100.0.1/30 broadcast 100.100.0.3

|

|||

|

|

Interface eth1 is up, line protocol detection is disabled

|

|||

|

|

Description: "test ip from provider A network"

|

|||

|

|

inet 100.100.1.1/24 broadcast 100.100.1.255

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show interface description

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Interface Status Protocol Description

|

|||

|

|

eth0 up unknown "to Router-B"

|

|||

|

|

eth1 up unknown "test ip from provider A network"

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

If everything looks alright, don't forget to save.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# write

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Repeat to configure interfaces on Router-B as well.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Before moving forward, verify that you can ping each other's IP address.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# ping 100.100.0.2

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

PING 100.100.0.2 (100.100.0.2) 56(84) bytes of data.

|

|||

|

|

64 bytes from 100.100.0.2: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.616 ms

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Next, we will move on to configure BGP peering and prefix advertisement settings.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Configuring BGP Peering ###

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The Quagga daemon responsible for BGP is called bgpd. First, we will prepare its configuration file.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# cp /usr/share/doc/quagga-XXXXXXX/bgpd.conf.sample /etc/quagga/bgpd.conf

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

On CentOS 6:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# service bgpd start

|

|||

|

|

# chkconfig bgpd on

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

For CentOS 7

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# systemctl start bgpd

|

|||

|

|

# systemctl enable bgpd

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Now, let's enter Quagga shell.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

# vtysh

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

First verify that there are no configured BGP sessions. In some versions, you may find a BGP session with AS 7675. We will remove it as we don't need it.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show running-config

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

... ... ...

|

|||

|

|

router bgp 7675

|

|||

|

|

bgp router-id 200.200.1.1

|

|||

|

|

... ... ...

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

We will remove any pre-configured BPG session, and replace it with our own.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# configure terminal

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# no router bgp 7675

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# router bgp 100

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# no auto-summary

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# no synchronizaiton

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config-router)# neighbor 100.100.0.2 remote-as 200

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config-router)# neighbor 100.100.0.2 description "provider B"

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config-router)# exit

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# exit

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# write

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-B should be configured in a similar way. The following configuration is provided as reference.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-B# configure terminal

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# no router bgp 7675

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# router bgp 200

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# no auto-summary

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# no synchronizaiton

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config-router)# neighbor 100.100.0.1 remote-as 100

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config-router)# neighbor 100.100.0.1 description "provider A"

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config-router)# exit

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# exit

|

|||

|

|

Router-B# write

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

When both routers are configured, a BGP peering between the two should be established. Let's verify that by running:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show ip bgp summary

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

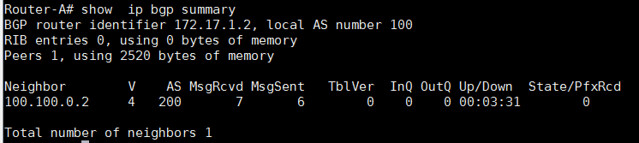

In the output, we should look at the section "State/PfxRcd." If the peering is down, the output will show 'Idle' or 'Active'. Remember, the word 'Active' inside a router is always bad. It means that the router is actively seeking for a neighbor, prefix or route. When the peering is up, the output under "State/PfxRcd" should show the number of prefixes received from this particular neighbor.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

In this example output, the BGP peering is just up between AS 100 and AS 200. Thus no prefixes are being exchanged, and the number in the rightmost column is 0.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Configuring Prefix Advertisements ###

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

As specified at the beginning, AS 100 will advertise a prefix 100.100.0.0/22, and AS 200 will advertise a prefix 200.200.0.0/22 in our example. Those prefixes need to be added to BGP configuration as follows.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

On Router-A:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# configure terminal

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# router bgp 100

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# network 100.100.0.0/22

|

|||

|

|

Router-A(config)# exit

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# write

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

On Router-B:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-B# configure terminal

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# router bgp 200

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# network 200.200.0.0/22

|

|||

|

|

Router-B(config)# exit

|

|||

|

|

Router-B# write

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

At this point, both routers should start advertising prefixes as required.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

### Testing Prefix Advertisements ###

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

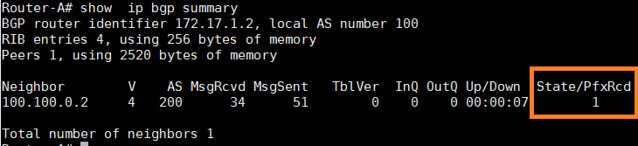

First of all, let's verify whether the number of prefixes has changed now.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show ip bgp summary

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

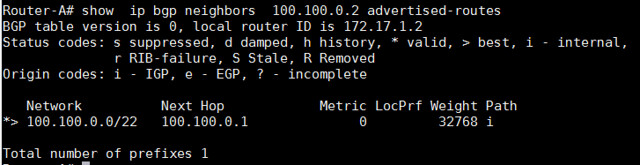

To view more details on the prefixes being received, we can use the following command, which shows the total number of prefixes received from neighbor 100.100.0.2.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show ip bgp neighbors 100.100.0.2 advertised-routes

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

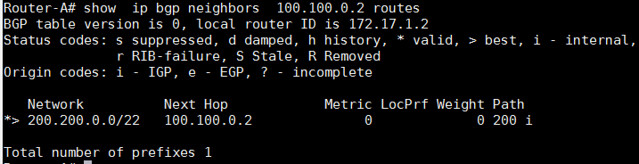

To check which prefixes we are receiving from that neighbor:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show ip bgp neighbors 100.100.0.2 routes

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

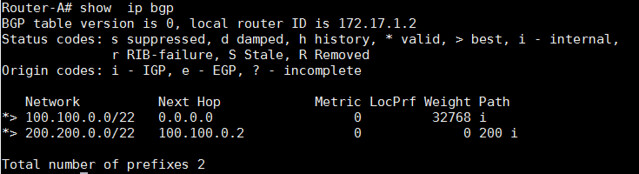

We can also check all the BGP routes:

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show ip bgp

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

These commands below can be used to check which routes in the routing table are learned via BGP.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show ip route

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Codes: K - kernel route, C - connected, S - static, R - RIP, O - OSPF,

|

|||

|

|

I - ISIS, B - BGP, > - selected route, * - FIB route

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

C>* 100.100.0.0/30 is directly connected, eth0

|

|||

|

|

C>* 100.100.1.0/24 is directly connected, eth1

|

|||

|

|

B>* 200.200.0.0/22 [20/0] via 100.100.0.2, eth0, 00:06:45

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Router-A# show ip route bgp

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

B>* 200.200.0.0/22 [20/0] via 100.100.0.2, eth0, 00:08:13

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

The BGP-learned routes should also be present in the Linux routing table.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

[root@Router-A~]# ip route

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

----------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

100.100.0.0/30 dev eth0 proto kernel scope link src 100.100.0.1

|

|||

|

|

100.100.1.0/24 dev eth1 proto kernel scope link src 100.100.1.1

|

|||

|

|

200.200.0.0/22 via 100.100.0.2 dev eth0 proto zebra

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Finally, we are going to test with ping command. ping should be successful.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

[root@Router-A~]# ping 200.200.1.1 -c 2

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

To sum up, this tutorial focused on how we can run basic BGP on a CentOS box. While this should get you started with BGP, there are other advanced settings such as prefix filters, BGP attribute tuning such as local preference and path prepend. I will be covering these topics in future tutorials.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Hope this helps.

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

via: http://xmodulo.com/centos-bgp-router-quagga.html

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

作者:[Sarmed Rahman][a]

|

|||

|

|

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

|||

|

|

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

[a]:http://xmodulo.com/author/sarmed

|

|||

|

|

[1]:http://xmodulo.com/turn-centos-box-into-ospf-router-quagga.html

|