mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-13 22:30:37 +08:00

115 lines

8.1 KiB

Markdown

115 lines

8.1 KiB

Markdown

|

|

How to clean up your data in the command line

|

||

|

|

======

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

I work part-time as a data auditor. Think of me as a proofreader who works with tables of data rather than pages of prose. The tables are exported from relational databases and are usually fairly modest in size: 100,000 to 1,000,000 records and 50 to 200 fields.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

I haven't seen an error-free data table, ever. The messiness isn't limited, as you might think, to duplicate records, spelling and formatting errors, and data items placed in the wrong field. I also find:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* broken records spread over several lines because data items had embedded line breaks

|

||

|

|

* data items in one field disagreeing with data items in another field, in the same record

|

||

|

|

* records with truncated data items, often because very long strings were shoehorned into fields with 50- or 100-character limits

|

||

|

|

* character encoding failures producing the gibberish known as [mojibake][1]

|

||

|

|

* invisible [control characters][2], some of which can cause data processing errors

|

||

|

|

* [replacement characters][3] and mysterious question marks inserted by the last program that failed to understand the data's character encoding

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Cleaning up these problems isn't hard, but there are non-technical obstacles to finding them. The first is everyone's natural reluctance to deal with data errors. Before I see a table, the data owners or managers may well have gone through all five stages of Data Grief:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

1. There are no errors in our data.

|

||

|

|

2. Well, maybe there are a few errors, but they're not that important.

|

||

|

|

3. OK, there are a lot of errors; we'll get our in-house people to deal with them.

|

||

|

|

4. We've started fixing a few of the errors, but it's time-consuming; we'll do it when we migrate to the new database software.

|

||

|

|

5. We didn't have time to clean the data when moving to the new database; we could use some help.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

The second progress-blocking attitude is the belief that data cleaning requires dedicated applications—either expensive proprietary programs or the excellent open source program [OpenRefine][4]. To deal with problems that dedicated applications can't solve, data managers might ask a programmer for help—someone good with [Python][5] or [R][6].

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

But data auditing and cleaning generally don't require dedicated applications. Plain-text data tables have been around for many decades, and so have text-processing tools. Open up a Bash shell and you have a toolbox loaded with powerful text processors like `grep`, `cut`, `paste`, `sort`, `uniq`, `tr`, and `awk`. They're fast, reliable, and easy to use.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

I do all my data auditing on the command line, and I've put many of my data-auditing tricks on a ["cookbook" website][7]. Operations I do regularly get stored as functions and shell scripts (see the example below).

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Yes, a command-line approach requires that the data to be audited have been exported from the database. And yes, the audit results need to be edited later within the database, or (database permitting) the cleaned data items need to be imported as replacements for the messy ones.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

But the advantages are remarkable. `awk` will process a few million records in seconds on a consumer-grade desktop or laptop. Uncomplicated regular expressions will find all the data errors you can imagine. And all of this will happen safely outside the database structure: Command-line auditing cannot affect the database, because it works with data liberated from its database prison.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Readers who trained on Unix will be smiling smugly at this point. They remember manipulating data on the command line many years ago in just these ways. What's happened since then is that processing power and RAM have increased spectacularly, and the standard command-line tools have been made substantially more efficient. Data auditing has never been faster or easier. And now that Microsoft Windows 10 can run Bash and GNU/Linux programs, Windows users can appreciate the Unix and Linux motto for dealing with messy data: Keep calm and open a terminal.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

![Tshirt, Keep Calm and Open A Terminal][9]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Photo by Robert Mesibov, CC BY

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### An example

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Suppose I want to find the longest data item in a particular field of a big table. That's not really a data auditing task, but it will show how shell tools work. For demonstration purposes, I'll use the tab-separated table `full0`, which has 1,122,023 records (plus a header line) and 49 fields, and I'll look in field number 36. (I get field numbers with a function explained [on my cookbook site][10].)

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

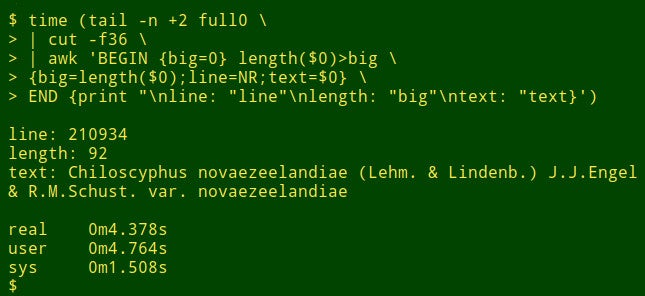

The command begins by using `tail` to remove the header line from `full0`. The result is piped to `cut`, which extracts the decapitated field 36. Next in the pipeline is `awk`. Here the variable `big` is initialized to a value of 0; then `awk` tests the length of the data item in the first record. If the length is bigger than 0, `awk` resets `big` to the new length and stores the line number (NR) in the variable `line` and the whole data item in the variable `text`. `awk` then processes each of the remaining 1,122,022 records in turn, resetting the three variables when it finds a longer data item. Finally, it prints out a neatly separated list of line numbers, length of data item, and full text of the longest data item. (In the following code, the commands have been broken up for clarity onto several lines.)

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

<code>tail -n +2 full0 \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

> | cut -f36 \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

> | awk 'BEGIN {big=0} length($0)>big \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

> {big=length($0);line=NR;text=$0} \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

> END {print "\nline: "line"\nlength: "big"\ntext: "text}' </code>

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

How long does this take? About 4 seconds on my desktop (core i5, 8GB RAM):

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

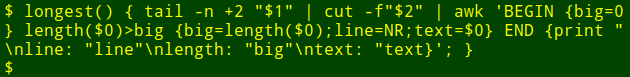

Now for the neat part: I can pop that long command into a shell function, `longest`, which takes as its arguments the filename `($1)` and the field number `($2)`:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

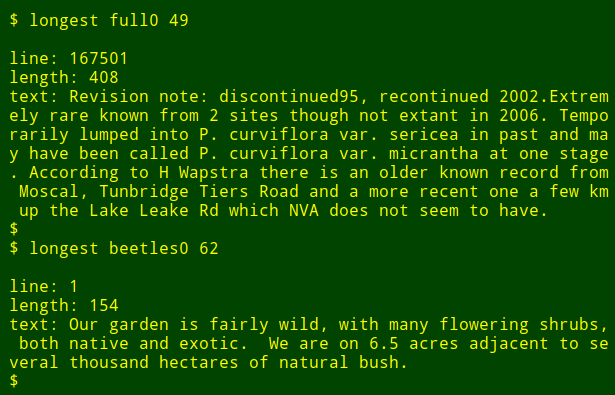

I can then re-run the command as a function, finding longest data items in other fields and in other files without needing to remember how the command is written:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

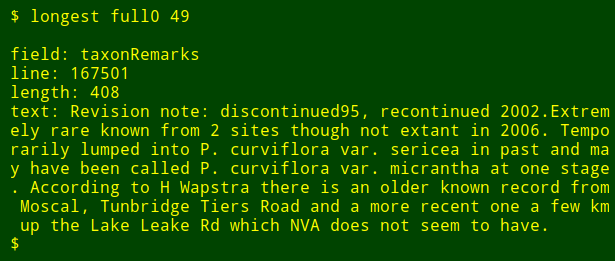

As a final tweak, I can add to the output the name of the numbered field I'm searching. To do this, I use `head` to extract the header line of the table, pipe that line to `tr` to convert tabs to new lines, and pipe the resulting list to `tail` and `head` to print the `$2th` field name on the list, where `$2` is the field number argument. The field name is stored in the shell variable `field` and passed to `awk` for printing as the internal `awk` variable `fld`.

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

<code>longest() { field=$(head -n 1 "$1" | tr '\t' '\n' | tail -n +"$2" | head -n 1); \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

tail -n +2 "$1" \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

| cut -f"$2" | \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

awk -v fld="$field" 'BEGIN {big=0} length($0)>big \

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

{big=length($0);line=NR;text=$0}

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

END {print "\nfield: "fld"\nline: "line"\nlength: "big"\ntext: "text}'; }</code>

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Note that if I'm looking for the longest data item in a number of different fields, all I have to do is press the Up Arrow key to get the last `longest` command, then backspace the field number and enter a new one.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/command-line-data-auditing

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

作者:[Bob Mesibov][a]

|

||

|

|

选题:[lujun9972](https://github.com/lujun9972)

|

||

|

|

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

|

|

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/bobmesibov

|

||

|

|

[1]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mojibake

|

||

|

|

[2]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Control_character

|

||

|

|

[3]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Specials_(Unicode_block)#Replacement_character

|

||

|

|

[4]:http://openrefine.org/

|

||

|

|

[5]:https://www.python.org/

|

||

|

|

[6]:https://www.r-project.org/about.html

|

||

|

|

[7]:https://www.polydesmida.info/cookbook/index.html

|

||

|

|

[8]:/file/399116

|

||

|

|

[9]:https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/terminal_tshirt.jpg (Tshirt, Keep Calm and Open A Terminal)

|

||

|

|

[10]:https://www.polydesmida.info/cookbook/functions.html#fields

|