mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-07 22:11:09 +08:00

403 lines

21 KiB

Markdown

403 lines

21 KiB

Markdown

|

|

translating by yongshouzhang

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

7 tools for analyzing performance in Linux with bcc/BPF

|

||

|

|

============================================================

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### Look deeply into your Linux code with these Berkeley Packet Filter (BPF) Compiler Collection (bcc) tools.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[][7] 21 Nov 2017 [Brendan Gregg][8] [Feed][9]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

43[up][10]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[4 comments][11]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Image by :

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

opensource.com

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

A new technology has arrived in Linux that can provide sysadmins and developers with a large number of new tools and dashboards for performance analysis and troubleshooting. It's called the enhanced Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF, or just BPF), although these enhancements weren't developed in Berkeley, they operate on much more than just packets, and they do much more than just filtering. I'll discuss one way to use BPF on the Fedora and Red Hat family of Linux distributions, demonstrating on Fedora 26.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

BPF can run user-defined sandboxed programs in the kernel to add new custom capabilities instantly. It's like adding superpowers to Linux, on demand. Examples of what you can use it for include:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* Advanced performance tracing tools: programmatic low-overhead instrumentation of filesystem operations, TCP events, user-level events, etc.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* Network performance: dropping packets early on to improve DDOS resilience, or redirecting packets in-kernel to improve performance

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* Security monitoring: 24x7 custom monitoring and logging of suspicious kernel and userspace events

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

BPF programs must pass an in-kernel verifier to ensure they are safe to run, making it a safer option, where possible, than writing custom kernel modules. I suspect most people won't write BPF programs themselves, but will use other people's. I've published many on GitHub as open source in the [BPF Compiler Collection (bcc)][12] project. bcc provides different frontends for BPF development, including Python and Lua, and is currently the most active project for BPF tooling.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 7 useful new bcc/BPF tools

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

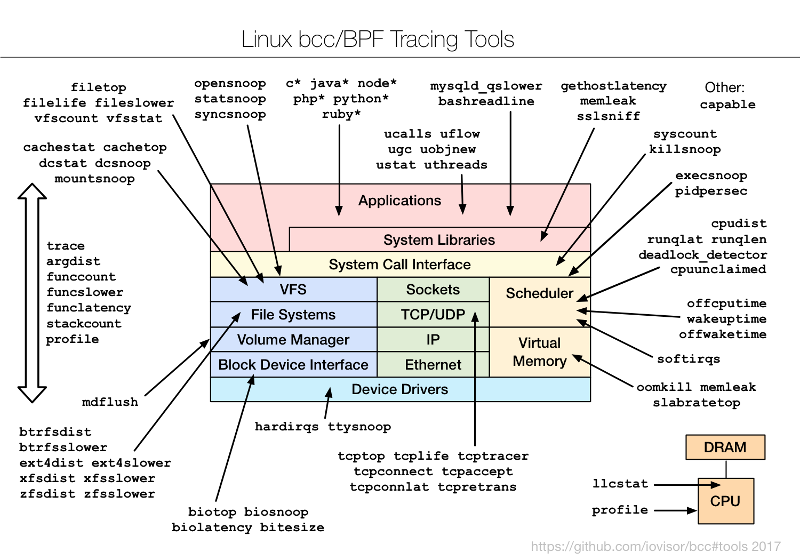

To understand the bcc/BPF tools and what they instrument, I created the following diagram and added it to the bcc project:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### [bcc_tracing_tools.png][13]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Brendan Gregg, [CC BY-SA 4.0][14]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

These are command-line interface (CLI) tools you can use over SSH (secure shell). Much analysis nowadays, including at my employer, is conducted using GUIs and dashboards. SSH is a last resort. But these CLI tools are still a good way to preview BPF capabilities, even if you ultimately intend to use them only through a GUI when available. I've began adding BPF capabilities to an open source GUI, but that's a topic for another article. Right now I'd like to share the CLI tools, which you can use today.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 1\. execsnoop

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Where to start? How about watching new processes. These can consume system resources, but be so short-lived they don't show up in top(1) or other tools. They can be instrumented (or, using the industry jargon for this, they can be traced) using [execsnoop][15]. While tracing, I'll log in over SSH in another window:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/execsnoop

|

||

|

|

PCOMM PID PPID RET ARGS

|

||

|

|

sshd 12234 727 0 /usr/sbin/sshd -D -R

|

||

|

|

unix_chkpwd 12236 12234 0 /usr/sbin/unix_chkpwd root nonull

|

||

|

|

unix_chkpwd 12237 12234 0 /usr/sbin/unix_chkpwd root chkexpiry

|

||

|

|

bash 12239 12238 0 /bin/bash

|

||

|

|

id 12241 12240 0 /usr/bin/id -un

|

||

|

|

hostname 12243 12242 0 /usr/bin/hostname

|

||

|

|

pkg-config 12245 12244 0 /usr/bin/pkg-config --variable=completionsdir bash-completion

|

||

|

|

grepconf.sh 12246 12239 0 /usr/libexec/grepconf.sh -c

|

||

|

|

grep 12247 12246 0 /usr/bin/grep -qsi ^COLOR.*none /etc/GREP_COLORS

|

||

|

|

tty 12249 12248 0 /usr/bin/tty -s

|

||

|

|

tput 12250 12248 0 /usr/bin/tput colors

|

||

|

|

dircolors 12252 12251 0 /usr/bin/dircolors --sh /etc/DIR_COLORS

|

||

|

|

grep 12253 12239 0 /usr/bin/grep -qi ^COLOR.*none /etc/DIR_COLORS

|

||

|

|

grepconf.sh 12254 12239 0 /usr/libexec/grepconf.sh -c

|

||

|

|

grep 12255 12254 0 /usr/bin/grep -qsi ^COLOR.*none /etc/GREP_COLORS

|

||

|

|

grepconf.sh 12256 12239 0 /usr/libexec/grepconf.sh -c

|

||

|

|

grep 12257 12256 0 /usr/bin/grep -qsi ^COLOR.*none /etc/GREP_COLORS

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Welcome to the fun of system tracing. You can learn a lot about how the system is really working (or not working, as the case may be) and discover some easy optimizations along the way. execsnoop works by tracing the exec() system call, which is usually used to load different program code in new processes.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 2\. opensnoop

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Continuing from above, so, grepconf.sh is likely a shell script, right? I'll run file(1) to check, and also use the [opensnoop][16] bcc tool to see what file is opening:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/opensnoop

|

||

|

|

PID COMM FD ERR PATH

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /etc/ld.so.cache

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /lib64/libmagic.so.1

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /lib64/libz.so.1

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /lib64/libc.so.6

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /usr/lib/locale/locale-archive

|

||

|

|

12420 file -1 2 /etc/magic.mgc

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /etc/magic

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /usr/share/misc/magic.mgc

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /usr/lib64/gconv/gconv-modules.cache

|

||

|

|

12420 file 3 0 /usr/libexec/grepconf.sh

|

||

|

|

1 systemd 16 0 /proc/565/cgroup

|

||

|

|

1 systemd 16 0 /proc/536/cgroup

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# file /usr/share/misc/magic.mgc /etc/magic

|

||

|

|

/usr/share/misc/magic.mgc: magic binary file for file(1) cmd (version 14) (little endian)

|

||

|

|

/etc/magic: magic text file for file(1) cmd, ASCII text

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 3\. xfsslower

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

bcc/BPF can analyze much more than just syscalls. The [xfsslower][17] tool traces common XFS filesystem operations that have a latency of greater than 1 millisecond (the argument):

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/xfsslower 1

|

||

|

|

Tracing XFS operations slower than 1 ms

|

||

|

|

TIME COMM PID T BYTES OFF_KB LAT(ms) FILENAME

|

||

|

|

14:17:34 systemd-journa 530 S 0 0 1.69 system.journal

|

||

|

|

14:17:35 auditd 651 S 0 0 2.43 audit.log

|

||

|

|

14:17:42 cksum 4167 R 52976 0 1.04 at

|

||

|

|

14:17:45 cksum 4168 R 53264 0 1.62 [

|

||

|

|

14:17:45 cksum 4168 R 65536 0 1.01 certutil

|

||

|

|

14:17:45 cksum 4168 R 65536 0 1.01 dir

|

||

|

|

14:17:45 cksum 4168 R 65536 0 1.17 dirmngr-client

|

||

|

|

14:17:46 cksum 4168 R 65536 0 1.06 grub2-file

|

||

|

|

14:17:46 cksum 4168 R 65536 128 1.01 grub2-fstest

|

||

|

|

[...]

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

This is a useful tool and an important example of BPF tracing. Traditional analysis of filesystem performance focuses on block I/O statistics—what you commonly see printed by the iostat(1) tool and plotted by many performance-monitoring GUIs. Those statistics show how the disks are performing, but not really the filesystem. Often you care more about the filesystem's performance than the disks, since it's the filesystem that applications make requests to and wait for. And the performance of filesystems can be quite different from that of disks! Filesystems may serve reads entirely from memory cache and also populate that cache via a read-ahead algorithm and for write-back caching. xfsslower shows filesystem performance—what the applications directly experience. This is often useful for exonerating the entire storage subsystem; if there is really no filesystem latency, then performance issues are likely to be elsewhere.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 4\. biolatency

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Although filesystem performance is important to study for understanding application performance, studying disk performance has merit as well. Poor disk performance will affect the application eventually, when various caching tricks can no longer hide its latency. Disk performance is also a target of study for capacity planning.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

The iostat(1) tool shows the average disk I/O latency, but averages can be misleading. It can be useful to study the distribution of I/O latency as a histogram, which can be done using [biolatency][18]:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/biolatency

|

||

|

|

Tracing block device I/O... Hit Ctrl-C to end.

|

||

|

|

^C

|

||

|

|

usecs : count distribution

|

||

|

|

0 -> 1 : 0 | |

|

||

|

|

2 -> 3 : 0 | |

|

||

|

|

4 -> 7 : 0 | |

|

||

|

|

8 -> 15 : 0 | |

|

||

|

|

16 -> 31 : 0 | |

|

||

|

|

32 -> 63 : 1 | |

|

||

|

|

64 -> 127 : 63 |**** |

|

||

|

|

128 -> 255 : 121 |********* |

|

||

|

|

256 -> 511 : 483 |************************************ |

|

||

|

|

512 -> 1023 : 532 |****************************************|

|

||

|

|

1024 -> 2047 : 117 |******** |

|

||

|

|

2048 -> 4095 : 8 | |

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

It's worth noting that many of these tools support CLI options and arguments as shown by their USAGE message:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/biolatency -h

|

||

|

|

usage: biolatency [-h] [-T] [-Q] [-m] [-D] [interval] [count]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Summarize block device I/O latency as a histogram

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

positional arguments:

|

||

|

|

interval output interval, in seconds

|

||

|

|

count number of outputs

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

optional arguments:

|

||

|

|

-h, --help show this help message and exit

|

||

|

|

-T, --timestamp include timestamp on output

|

||

|

|

-Q, --queued include OS queued time in I/O time

|

||

|

|

-m, --milliseconds millisecond histogram

|

||

|

|

-D, --disks print a histogram per disk device

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

examples:

|

||

|

|

./biolatency # summarize block I/O latency as a histogram

|

||

|

|

./biolatency 1 10 # print 1 second summaries, 10 times

|

||

|

|

./biolatency -mT 1 # 1s summaries, milliseconds, and timestamps

|

||

|

|

./biolatency -Q # include OS queued time in I/O time

|

||

|

|

./biolatency -D # show each disk device separately

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 5\. tcplife

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Another useful tool and example, this time showing lifespan and throughput statistics of TCP sessions, is [tcplife][19]:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/tcplife

|

||

|

|

PID COMM LADDR LPORT RADDR RPORT TX_KB RX_KB MS

|

||

|

|

12759 sshd 192.168.56.101 22 192.168.56.1 60639 2 3 1863.82

|

||

|

|

12783 sshd 192.168.56.101 22 192.168.56.1 60640 3 3 9174.53

|

||

|

|

12844 wget 10.0.2.15 34250 54.204.39.132 443 11 1870 5712.26

|

||

|

|

12851 curl 10.0.2.15 34252 54.204.39.132 443 0 74 505.90

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 6\. gethostlatency

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Every previous example involves kernel tracing, so I need at least one user-level tracing example. Here is [gethostlatency][20], which instruments gethostbyname(3) and related library calls for name resolution:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/gethostlatency

|

||

|

|

TIME PID COMM LATms HOST

|

||

|

|

06:43:33 12903 curl 188.98 opensource.com

|

||

|

|

06:43:36 12905 curl 8.45 opensource.com

|

||

|

|

06:43:40 12907 curl 6.55 opensource.com

|

||

|

|

06:43:44 12911 curl 9.67 opensource.com

|

||

|

|

06:45:02 12948 curl 19.66 opensource.cats

|

||

|

|

06:45:06 12950 curl 18.37 opensource.cats

|

||

|

|

06:45:07 12952 curl 13.64 opensource.cats

|

||

|

|

06:45:19 13139 curl 13.10 opensource.cats

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### 7\. trace

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Okay, one more example. The [trace][21] tool was contributed by Sasha Goldshtein and provides some basic printf(1) functionality with custom probes. For example:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/trace 'pam:pam_start "%s: %s", arg1, arg2'

|

||

|

|

PID TID COMM FUNC -

|

||

|

|

13266 13266 sshd pam_start sshd: root

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### Install bcc via packages

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

The best way to install bcc is from an iovisor repository, following the instructions from the bcc [INSTALL.md][22]. [IO Visor][23] is the Linux Foundation project that includes bcc. The BPF enhancements these tools use were added in the 4.x series Linux kernels, up to 4.9\. This means that Fedora 25, with its 4.8 kernel, can run most of these tools; and Fedora 26, with its 4.11 kernel, can run them all (at least currently).

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

If you are on Fedora 25 (or Fedora 26, and this post was published many months ago—hello from the distant past!), then this package approach should just work. If you are on Fedora 26, then skip to the [Install via Source][24] section, which avoids a [known][25] and [fixed][26] bug. That bug fix hasn't made its way into the Fedora 26 package dependencies at the moment. The system I'm using is:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# uname -a

|

||

|

|

Linux localhost.localdomain 4.11.8-300.fc26.x86_64 #1 SMP Thu Jun 29 20:09:48 UTC 2017 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/Linux

|

||

|

|

# cat /etc/fedora-release

|

||

|

|

Fedora release 26 (Twenty Six)

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# echo -e '[iovisor]\nbaseurl=https://repo.iovisor.org/yum/nightly/f25/$basearch\nenabled=1\ngpgcheck=0' | sudo tee /etc/yum.repos.d/iovisor.repo

|

||

|

|

# dnf install bcc-tools

|

||

|

|

[...]

|

||

|

|

Total download size: 37 M

|

||

|

|

Installed size: 143 M

|

||

|

|

Is this ok [y/N]: y

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# ls /usr/share/bcc/tools/

|

||

|

|

argdist dcsnoop killsnoop softirqs trace

|

||

|

|

bashreadline dcstat llcstat solisten ttysnoop

|

||

|

|

[...]

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/opensnoop

|

||

|

|

chdir(/lib/modules/4.11.8-300.fc26.x86_64/build): No such file or directory

|

||

|

|

Traceback (most recent call last):

|

||

|

|

File "/usr/share/bcc/tools/opensnoop", line 126, in

|

||

|

|

b = BPF(text=bpf_text)

|

||

|

|

File "/usr/lib/python3.6/site-packages/bcc/__init__.py", line 284, in __init__

|

||

|

|

raise Exception("Failed to compile BPF module %s" % src_file)

|

||

|

|

Exception: Failed to compile BPF module

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# dnf install kernel-devel-4.11.8-300.fc26.x86_64

|

||

|

|

[...]

|

||

|

|

Total download size: 20 M

|

||

|

|

Installed size: 63 M

|

||

|

|

Is this ok [y/N]: y

|

||

|

|

[...]

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/opensnoop

|

||

|

|

PID COMM FD ERR PATH

|

||

|

|

11792 ls 3 0 /etc/ld.so.cache

|

||

|

|

11792 ls 3 0 /lib64/libselinux.so.1

|

||

|

|

11792 ls 3 0 /lib64/libcap.so.2

|

||

|

|

11792 ls 3 0 /lib64/libc.so.6

|

||

|

|

[...]

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### Install via source

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

If you need to install from source, you can also find documentation and updated instructions in [INSTALL.md][27]. I did the following on Fedora 26:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

sudo dnf install -y bison cmake ethtool flex git iperf libstdc++-static \

|

||

|

|

python-netaddr python-pip gcc gcc-c++ make zlib-devel \

|

||

|

|

elfutils-libelf-devel

|

||

|

|

sudo dnf install -y luajit luajit-devel # for Lua support

|

||

|

|

sudo dnf install -y \

|

||

|

|

http://pkgs.repoforge.org/netperf/netperf-2.6.0-1.el6.rf.x86_64.rpm

|

||

|

|

sudo pip install pyroute2

|

||

|

|

sudo dnf install -y clang clang-devel llvm llvm-devel llvm-static ncurses-devel

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

Curl error (28): Timeout was reached for http://pkgs.repoforge.org/netperf/netperf-2.6.0-1.el6.rf.x86_64.rpm [Connection timed out after 120002 milliseconds]

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Here are the remaining bcc compilation and install steps:

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

git clone https://github.com/iovisor/bcc.git

|

||

|

|

mkdir bcc/build; cd bcc/build

|

||

|

|

cmake .. -DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=/usr

|

||

|

|

make

|

||

|

|

sudo make install

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

# /usr/share/bcc/tools/opensnoop

|

||

|

|

PID COMM FD ERR PATH

|

||

|

|

4131 date 3 0 /etc/ld.so.cache

|

||

|

|

4131 date 3 0 /lib64/libc.so.6

|

||

|

|

4131 date 3 0 /usr/lib/locale/locale-archive

|

||

|

|

4131 date 3 0 /etc/localtime

|

||

|

|

[...]

|

||

|

|

```

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

More Linux resources

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* [What is Linux?][1]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* [What are Linux containers?][2]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* [Download Now: Linux commands cheat sheet][3]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* [Advanced Linux commands cheat sheet][4]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* [Our latest Linux articles][5]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

This was a quick tour of the new BPF performance analysis superpowers that you can use on the Fedora and Red Hat family of operating systems. I demonstrated the popular

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[bcc][28]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

frontend to BPF and included install instructions for Fedora. bcc comes with more than 60 new tools for performance analysis, which will help you get the most out of your Linux systems. Perhaps you will use these tools directly over SSH, or perhaps you will use the same functionality via monitoring GUIs once they support BPF.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Also, bcc is not the only frontend in development. There are [ply][29] and [bpftrace][30], which aim to provide higher-level language for quickly writing custom tools. In addition, [SystemTap][31] just released [version 3.2][32], including an early, experimental eBPF backend. Should this continue to be developed, it will provide a production-safe and efficient engine for running the many SystemTap scripts and tapsets (libraries) that have been developed over the years. (Using SystemTap with eBPF would be good topic for another post.)

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

If you need to develop custom tools, you can do that with bcc as well, although the language is currently much more verbose than SystemTap, ply, or bpftrace. My bcc tools can serve as code examples, plus I contributed a [tutorial][33] for developing bcc tools in Python. I'd recommend learning the bcc multi-tools first, as you may get a lot of mileage from them before needing to write new tools. You can study the multi-tools from their example files in the bcc repository: [funccount][34], [funclatency][35], [funcslower][36], [stackcount][37], [trace][38], and [argdist][39].

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Thanks to [Opensource.com][40] for edits.

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### Topics

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[Linux][41][SysAdmin][42]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

### About the author

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[][43] Brendan Gregg

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

-

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Brendan Gregg is a senior performance architect at Netflix, where he does large scale computer performance design, analysis, and tuning.[More about me][44]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

* [Learn how you can contribute][6]

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

via:https://opensource.com/article/17/11/bccbpf-performance

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

作者:[Brendan Gregg ][a]

|

||

|

|

译者:[yongshouzhang](https://github.com/yongshouzhang)

|

||

|

|

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

[a]:

|

||

|

|

[1]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-is-linux?intcmp=70160000000h1jYAAQ&utm_source=intcallout&utm_campaign=linuxcontent

|

||

|

|

[2]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-are-linux-containers?intcmp=70160000000h1jYAAQ&utm_source=intcallout&utm_campaign=linuxcontent

|

||

|

|

[3]:https://developers.redhat.com/promotions/linux-cheatsheet/?intcmp=70160000000h1jYAAQ&utm_source=intcallout&utm_campaign=linuxcontent

|

||

|

|

[4]:https://developers.redhat.com/cheat-sheet/advanced-linux-commands-cheatsheet?intcmp=70160000000h1jYAAQ&utm_source=intcallout&utm_campaign=linuxcontent

|

||

|

|

[5]:https://opensource.com/tags/linux?intcmp=70160000000h1jYAAQ&utm_source=intcallout&utm_campaign=linuxcontent

|

||

|

|

[6]:https://opensource.com/participate

|

||

|

|

[7]:https://opensource.com/users/brendang

|

||

|

|

[8]:https://opensource.com/users/brendang

|

||

|

|

[9]:https://opensource.com/user/77626/feed

|

||

|

|

[10]:https://opensource.com/article/17/11/bccbpf-performance?rate=r9hnbg3mvjFUC9FiBk9eL_ZLkioSC21SvICoaoJjaSM

|

||

|

|

[11]:https://opensource.com/article/17/11/bccbpf-performance#comments

|

||

|

|

[12]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc

|

||

|

|

[13]:https://opensource.com/file/376856

|

||

|

|

[14]:https://opensource.com/usr/share/bcc/tools/trace

|

||

|

|

[15]:https://github.com/brendangregg/perf-tools/blob/master/execsnoop

|

||

|

|

[16]:https://github.com/brendangregg/perf-tools/blob/master/opensnoop

|

||

|

|

[17]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/xfsslower.py

|

||

|

|

[18]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/biolatency.py

|

||

|

|

[19]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/tcplife.py

|

||

|

|

[20]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/gethostlatency.py

|

||

|

|

[21]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/trace.py

|

||

|

|

[22]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/INSTALL.md#fedora---binary

|

||

|

|

[23]:https://www.iovisor.org/

|

||

|

|

[24]:https://opensource.com/article/17/11/bccbpf-performance#InstallViaSource

|

||

|

|

[25]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/issues/1221

|

||

|

|

[26]:https://reviews.llvm.org/rL302055

|

||

|

|

[27]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/INSTALL.md#fedora---source

|

||

|

|

[28]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc

|

||

|

|

[29]:https://github.com/iovisor/ply

|

||

|

|

[30]:https://github.com/ajor/bpftrace

|

||

|

|

[31]:https://sourceware.org/systemtap/

|

||

|

|

[32]:https://sourceware.org/ml/systemtap/2017-q4/msg00096.html

|

||

|

|

[33]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/docs/tutorial_bcc_python_developer.md

|

||

|

|

[34]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/funccount_example.txt

|

||

|

|

[35]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/funclatency_example.txt

|

||

|

|

[36]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/funcslower_example.txt

|

||

|

|

[37]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/stackcount_example.txt

|

||

|

|

[38]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/trace_example.txt

|

||

|

|

[39]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/argdist_example.txt

|

||

|

|

[40]:http://opensource.com/

|

||

|

|

[41]:https://opensource.com/tags/linux

|

||

|

|

[42]:https://opensource.com/tags/sysadmin

|

||

|

|

[43]:https://opensource.com/users/brendang

|

||

|

|

[44]:https://opensource.com/users/brendang

|